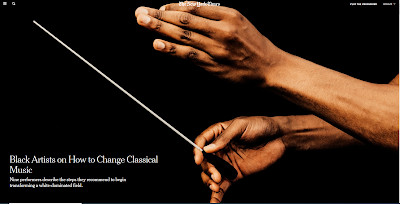

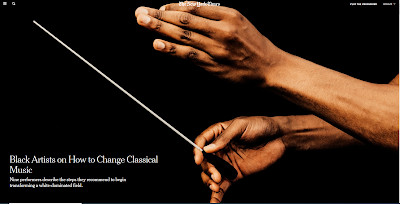

The conductor Roderick Cox.

Credit...Mustafah Abdulaziz for The New York Times

With their major

institutions founded on white European models and obstinately focused

on the distant past, classical music and opera have been even slower

than American society at large to confront racial inequity. Black

players make up less than 2 percent of the nation’s orchestras; the Metropolitan Opera still has yet to put on a work by a Black composer.

The

protests against police brutality and racial exclusion that have

engulfed the country since the end of May have encouraged individuals

and organizations toward new awareness of long-held biases, and provided

new motivation to change. Nine Black performers spoke with The New York

Times about steps that could be taken to begin transforming a

white-dominated field. These are edited excerpts from the conversations.

[Bassoonist] Monica Ellis in Harlem this month.Credit...Wayne Lawrence for The New York Times

The first step is admitting that these organizations are built on a

white framework built to benefit white people. Have you done the work to

create a structure that is actually benefiting Black and brown

communities? When that occurs, diversity is a natural byproduct. There

needs to be intentional hiring of qualified Black musicians who you know

are going to bring the goods to your audiences.

Thomas Wilkins conducting the Omaha Symphony, where he is music director, last year.Credit...Casey Wood

It’s incumbent upon leadership from the podium to be part of this: who

gets hired, what repertory gets played, where the orchestra plays. If

you’re not willing, for example, to have minority music interns playing

subscription concerts because they didn’t take the audition, that

doesn’t make any sense to me. This person needs the opportunity to play

this repertoire; you have to be willing to let that happen, and you

can’t bow to blowback from the full-time players.

Jessie Montgomery in Princeton, N.J., this month.Credit...Wayne Lawrence for The New York Times

I’m in my fifth year on the board of Chamber Music America, and more

than half the board is people of color. It’s very evenly balanced as far

as gender and race; those changes were implemented through consulting

work and training, and facilitated discussions among the board to make

sure everyone was on the same page.

[Conductor] Roderick Cox in Berlin this month.Credit...Mustafah Abdulaziz for The New York Times

I would like changes to be made in how we train musicians in

conservatories and universities. A lot of our thinking, and our

perceptions of what’s good music, becomes indoctrinated at that stage. I

say this because even though I’m a person of color, I was guilty of not

being accepting of new voices and styles outside of Beethoven,

Schumann, all the usual music of the past. When we start with

preconceived notions, we limit ourselves. People are afraid of being

uncomfortable, but with discomfort comes growth.

[Clarinetist] Anthony McGill in the Bronx this month.Credit...Miranda Barnes for The New York Times

Over the last month, you’ve seen all these outpourings, and it’s in

these moments when you see: Are we really connected with the communities

we’re doing this work in? At the New York Philharmonic, where I am

principal clarinet, I think there’s been incentive to partner up with

the Harmony Program, which does after-school music education.

[Singer] Lawrence Brownlee performing at the Church of the Intercession in Manhattan in 2018.Credit...Steven Pisano

Artistic institutions need to be focused on representing and really

serving the communities that they’re in. There needs to be community

engagement, not community outreach. Outreach is something you do

occasionally. But you’re always in the act of engaging; it’s a constant

effort.

[Composer] Terence Blanchard at a recording session for the Spike Lee film “Da 5 Bloods” last year.Credit...Matt Sayles/Netflix

It’s like anything else: The organizations need to represent what

America looks like. Well-intentioned people can just have blinders on. I

don’t look at it like a sinister plot; I look at it as people are going

with what they’re comfortable with. If we had more representation in

the leadership, in terms of who is signing off on projects, you’ll have

more people bringing things to the table. What I saw at Opera Theater of

St. Louis — where I did “Champion” and “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,”

which is going to the Met — is those people are open to a lot of ideas.

[Singer] Latonia Moore in Miami this month.Credit...Jeffery Salter for The New York Times

Please, in the future, cast with your heart, not just with your eyes and

your ears. Who gives you the goose bumps? Pick them. Some people see a

Black tenor, and they think Otello. Or they see a Black soprano and they

think Aida. “Who wants to see a Black Cio-Cio San?” You’ll hear that.

But yes, opera is a suspension of disbelief.

[Composer] Tania León in Nyack, N.Y., this month.Credit...Miranda Barnes for The New York Times

Certain groups of people have felt that they did not belong, because

most of the time they didn’t see people who resembled them onstage. But

even if things look good onstage, internally is that what is happening

in the institution? It’s a family type of thing. That person working in

the office goes home and tells the people at home, and they usually have

other friends. That is how audiences change. It has to be from the

inside out.

No comments:

Post a Comment