And The

VEXED FATE

of

BLACK CLASSICAL

MUSIC

JOSEPH

HOROWITZ

WITH A FOREWORD BY GEORGE SHIRLEY

January 3, 2022

By Ralph P. Locke

Joseph Horowitz’s short, punchy, well-sourced, and compulsively readable book argues for bringing back the forgotten works of important Black composers.

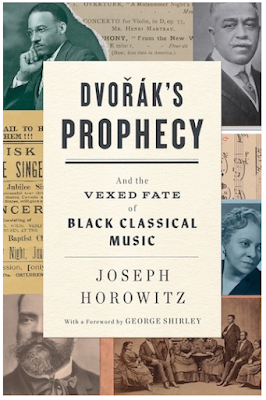

Dvořák’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music by Joseph Horowitz. W. W. Norton, 229 pp., $30 (hardcover).

For several years, newspapers and social media have drawn attention to the relative absence of African-Americans within the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and within the list of nominees (and hence winners) for the Oscars. As a result, some progress is beginning to be made. A similar challenge, but regarding the classical-music industry, has been presented by music critic Joseph Horowitz over the past two decades in a series of articles, books, and festivals.

Horowitz’s latest book — short, punchy, well-sourced, and compulsively readable, if loosely structured — argues for bringing back the forgotten works of important Black composers such as Harry (Henry T.) Burleigh, Florence B. Price, R. Nathaniel Dett, William Levi Dawson, Margaret Bonds, and William Grant Still, along with those of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a Black British composer whose oratorio Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast was performed rather often here a century ago.

The volume touches on many other topics, notably the longstanding tendency of the classical-music establishment, over the past century, to favor music that displays high modernist complexity and to sneer at, or simply ignore, works that are written in an easily accessible style using — even if in fresh and rejuvenating ways — familiar harmonies and easily grasped melodies. Horowitz argues that the American classical-music industry has consistently suppressed or rejected any and all attempts at creating a distinctive American style of composition that connected with musical styles and genres widely enjoyed by the broad public. These accessible styles and genres not only included the living stream of African-American music (e.g., “Negro spirituals” and early jazz) but whole swaths of “mainstream” musical practice, including popular song, commercial dance music, the Broadway musical, and the hymn tunes of white churches.

That line of Horowitz’s argument directly connects to the book’s title. The composers I named at the outset were all primarily traditionalist, rather than modernist, in orientation. But the critic also devotes much attention to composers who were not Black. He makes the case for recognizing the symphonies of Charles Ives for their fresh and compelling uses of relatively accessible materials (e.g., catchy college tunes, or the rhythms and phrase structures familiar from marches, social dances, and — here’s where African-American music comes into this particular case — ragtime). Thus he believes that we should appreciate, not castigate, George Gershwin for making imaginative and powerful use of African-American “sorrow songs” (once widely known as “Negro spirituals”) in Porgy and Bess and of jazz elements in Rhapsody in Blue and the Piano Concerto in F.

Horowitz is undoubtedly correct. Self-appointed American tastemakers — concert organizers, conductors, conservatory directors, music critics, women’s music-club members, and so on — long insisted that European models of musical “high culture” be rigidly followed. This policy was carried out in the ensuing decades — at an increasingly high technical and interpretive level — by solo performers, symphony orchestras, and opera companies as well as by the composition departments of many music schools.

One particularly unfortunate result has been (to go back to the book’s title) a severing of the natural and productive bond between members of the African-American community and the classical-music world, a bond that was emphatically encouraged by Czech composer Antonín Dvořák during his two-plus years in the US and that, for a time, did exist, beginning with Dvořák’s talented and determined student Harry Burleigh.

***

In recent years, individual performers and groups have been programming and recording — partly in response to the Black Lives Matter movement — significant but little-known or even newly discovered pieces by notable Black composers. Some of the artists are Black (such as prominent young baritone Will Liverman) or not (the somewhat more established baritone Lucas Meachem). Some of the recordings are on major labels (Deutsche Grammophon’s release of Symphonies 1 and 3 by Florence Price, with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Canadian-born Yannick Nizet-Séguin). At least two (the Liverman and Florence Price recordings just mentioned) have recently been recognized by Grammy nominations. And the Buffalo Philharmonic has just announced its latest release (to be available through Naxos) of works by six composers: Bach, Haydn, Vaughan-Williams, and American composers Wayne Barlow, Ulysses Kay, and George Walker. Kay and Walker were perhaps the most prominent Black composers of concert music in the late twentieth century. The Kay work, Pietà, for English horn and orchestra, is a recorded premiere.

No comments:

Post a Comment