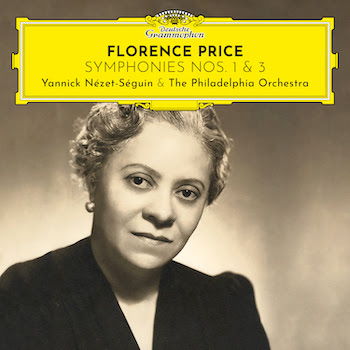

Symphonies Nos. 1 & 3

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Recordings of Florence Price’s symphonies by top-tier professional orchestras have been a long time coming. Granted, this music has been kept alive of late by the admirable efforts of some regional and international ensembles (particularly John Jeter and the Fort Smith Symphony in Arkansas). But, given Price’s reputation as the United States’ first important African American woman composer, her output surely deserves wider advocacy.

Enter Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra, who are now helming the first recorded cycle of Price’s symphonic works by a major American orchestra.

The results of their first release, which pairs her Symphonies nos. 1 and 3, are revealing.

To be sure, Price’s music has never sounded better. The Philadelphians’ playing is technically impeccable, carefully balanced, and smartly shaped. For warmth of tone, continuity of sound, and delicacy of phrasing, one can hardly imagine either piece being more flatteringly presented.

At the same time, the excellence of these performances highlight some of the weaknesses of Price’s technique.

Chief among them is that, while she was a gifted miniaturist, Price was no natural symphonist.

Take the E-minor Symphony no. 1. Written in 1933 and premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Frederick Stock, it’s plenty ambitious, lasting nearly forty minutes.

Yet at least a third of that duration is digressive; most of it, in fact, the fault of the first movement. Here, Price follows symphonic sonata form to a T: there are contrasting subjects in two key areas, an exposition repeat, a busy development, a recapitulation of the opening materials, and a blazing coda. On paper, then, a textbook symphonic movement.

Having said all of that, Price’s First is no flop. Quite the opposite: apart from the overlong first movement, it’s a beguiling essay. Her orchestrations, if not always inspired, display – even in that meandering first movement – an ingenious ear for color (like the appearance of chimes and celesta in the development) and texture (vaguely Ivesian clarinet shadow lines pop up periodically).

Best, once you get to the inner movements – which draw more clearly on her African American heritage and experience as a church musician – the piece takes on a different cast entirely.

The second movement, with its call-and-response structure, strong contrast of thematic ideas, and creative scoring is beautiful: in the present recording, you can hear all the moving melodic lines. And, despite the occasional busy-ness of the registrations, the Philadelphians’ woodwind solos are luminously done.

For the third movement, Price drew on the African Juba dance. Agile and fresh, this music offers lots of repetition but enough variation in the orchestration so as not to become redundant – as well as spry syncopations and layers of rhythmic complexity throughout.

No comments:

Post a Comment